My plan was to stay in Spain for one year. I thought it was my only opportunity to live in Europe. My goals? Travel. Party. Make a bunch of friends. Fall in love. Try to enjoy teaching again.

It was August 2019, and I had 7 months left of being 29. 7 months left of society still thinking I’m young, beautiful, and a ravishing rebel without a cause. I figured that, once I turned 30, society would deem me overnight old, ugly, and irresponsible. What would I do when I turned 30 and my visa expired? Where would I live? Who cares when you’re in Madrid and the wine is cheap, the men are beautiful, and every day feels like a dream?

Madrid was my oyster, and I was grabbing as much as I could, headfirst and hands full. Every date, every drink, every discoteca, every experience–it was mine for the taking. And oh, my, was Madrid gorgeous.

I loved the nightlife, but I hated the nights. Nights were the moments when I cried myself to sleep over my situationship that ended three days before my flight. I thought absence would make the heart grow fonder. Turns out, it doesn’t. No problem. Nothing heals heartbreak like a Jack and Coke in a bar so loud I can’t hear my thoughts.

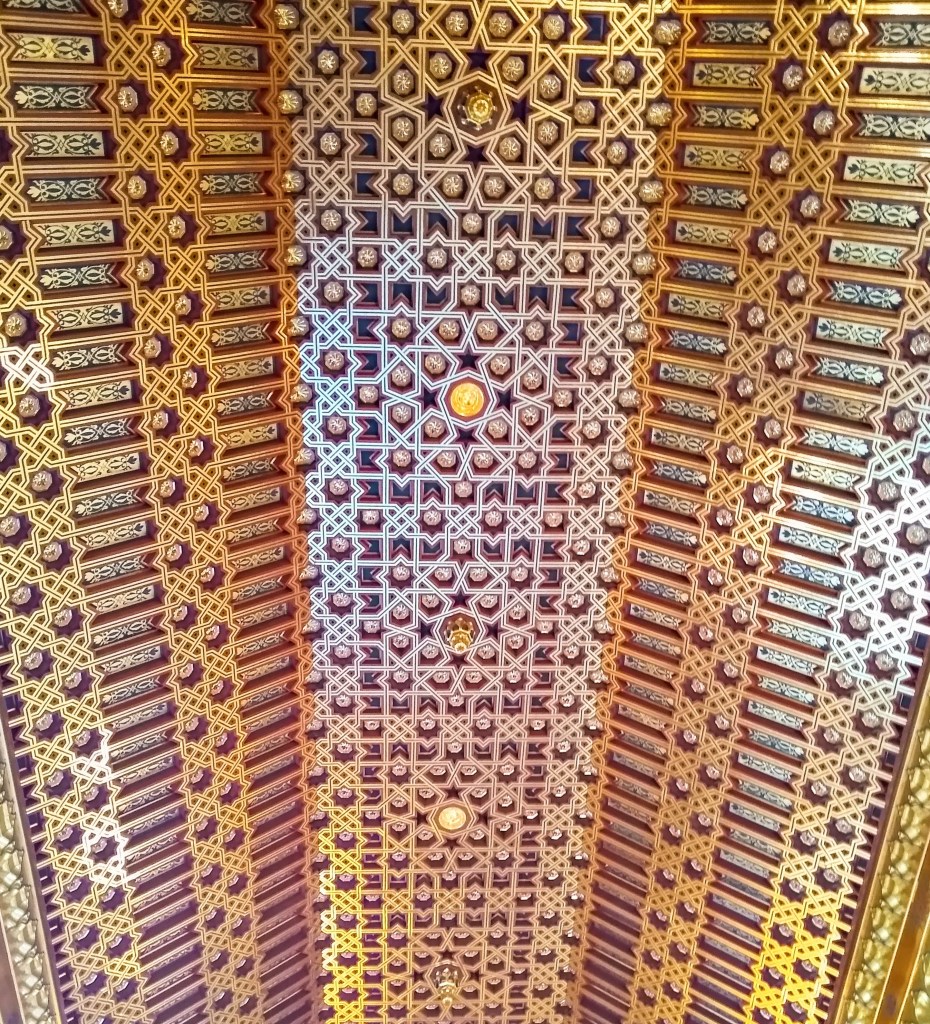

When my new friends and I weren’t living it up in the nightlife, we were exploring Spain by day. Cities older than my country. Castles and wine and all the wonderfulness I’d imagined all these years, but never thought I’d see face to face.

But wait–didn’t I come to Spain to teach?

There were 8 teachers in my program, including me, and most were fresh out of college. One of the girls and I lived in an apartment in Salamanca, the bougie area of Madrid. We lucked out on location and great roommates.

Before Spain, I’d almost quit teaching. My stress and anxiety woke me up in the middle of the night. My curves had melted off my body from my loss of appetite, leaving me waif and washed out. I didn’t miss angry emails or endless paperwork or mind-numbing meetings.

Teaching business English was a breath of fresh air.

How’s this for irony: I didn’t want to work in corporate, but loved teaching students in corporate. My class sizes ranged from 1-4 students. No meetings, no grades to submit—just helping my students use English well at their jobs. This was much more enjoyable.

I’d spend 2-3 hours per day underground in the Madrid metro, but I didn’t mind. It felt like a video game: would I get a seat? How long would it take to switch from line 6 to line 10? Would I make it before the metro car doors shut in my face?

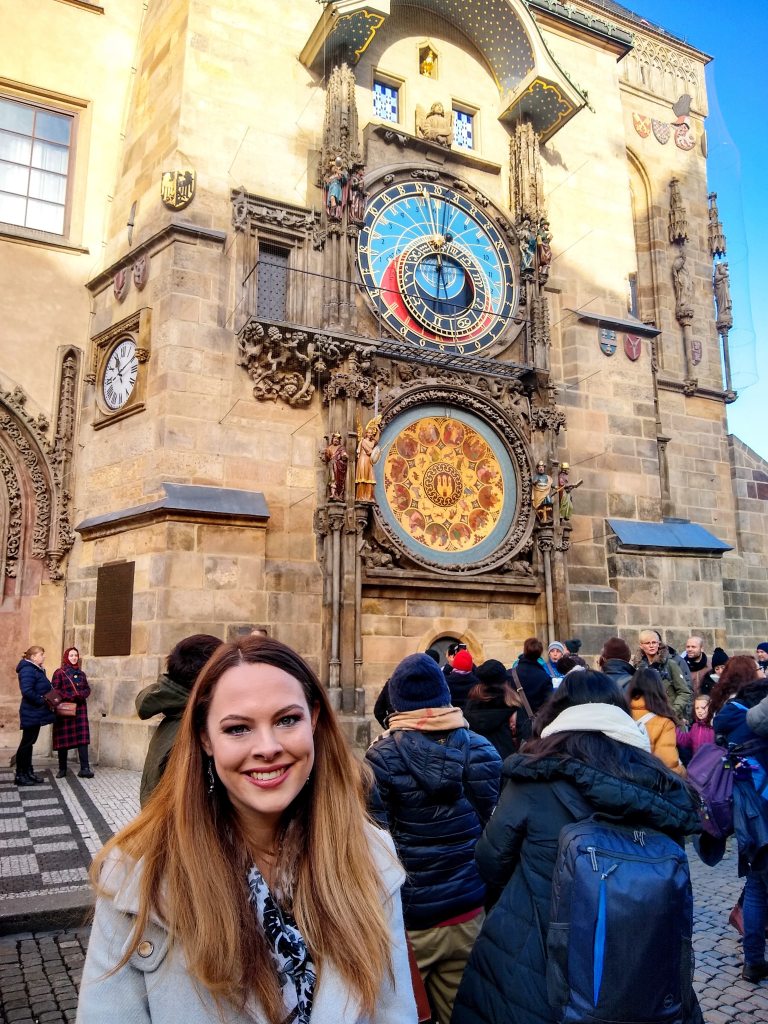

I like to call this my Gastby Era. Business English teacher mogul by day, jet-setter by night. High heels, size 2 dresses, and trips on a whim to Austria and Romania and spending Christmas in Prague and Berlin. Ringing in the New Year in Sol, the heart of Madrid.

I was healing from heartbreak, and I got a new boyfriend after Valentine’s Day. It was with him that I saw the Mediterranean Sea for the first time. The wind that day was ferocious, and we stood in front of the blue, and I hugged him so tightly, fearing that if I let go, Mother Nature would take us back to her womb. Or wake me up from what felt like a dream come true.

“I feel like we’ve been waiting a long time to find someone like each other,” he told me one night in Andalusia, as we rode off into the starry night.

Those words melted in my mind like candy in my mouth. I felt the pain from my situationship fade into the Milky Way millions of miles above me.

Life felt incredible. I felt unstoppable.

Then covid happened.

Fast forward to March 2020. Travel—no. Parties—no. Friends—they all left. Teaching—I nearly lost all my classes, and at one point, had five dollars in my bank account.

Did you hear me right? Five dollars. That wasn’t even five euros.

I had no idea how I was going to survive.

And I didn’t dare tell anyone back in the United States how dire my situation had become.

The lockdown in Spain was one of the strictest in Europe. We couldn’t go outside unless we were going to the supermarket or the pharmacy. We couldn’t even go up and down the stairs in our apartment buildings.

Once my friends left, I spent two months in my room, all alone, with almost nothing to do. Oh, and that new boyfriend? Gone, too.

Then, the one friend I had left in Madrid and I had a fallout. No one told me friend breakups hurt more than boyfriend breakups.

So now I was really alone.

Looking back, this period of nothingness was the rest I’d need to survive the next four years of my life.

After a financial drought, I started teaching online. I’d start as early as six in the morning, and finish as late as eleven at night. Money came in—trickling like rainwater, but it came in. I was able to pay my rent and buy food that was more flavorful than the rice and ketchup I’d been feasting on.

I taught online all summer. Up by 5:30am, force-feed instant coffee, teach, take a break, have a minor existential crisis, resume teaching until 6:30, sweat in front of a fan for a few hours, resume teaching, finish at 11:00pm, turn off my overheated laptop with a broken screen, collapse on my bed feeling comatose. Rinse and repeat.

In the few moments I did muster the energy to go outside, I’d walk in my bougie neighborhood, flabbergasted that I was living in a champagne neighborhood on a beer budget. I couldn’t even have moved if I’d wanted to, though, because I didn’t have the money for the next month’s rent and a deposit. But I didn’t mind. My neighborhood reminded me that, even in moments of uncertainty, beauty was still all around me.

After two months with barely any days off, I traveled to San Sebastian, in the north of Spain, on a whim at the end of August. I also visited Hondarribia, a town bordering France. I was so close to France I could have swum there.

It would be the last time I’d be able to leave Madrid for almost a year. The pandemic was about to pick up speed.

I was about to start student teaching at an elementary school. In the midst of nothingness, I’d been given an opportunity—another year in Madrid. I didn’t have any friends, but I was sure I’d find some. I’d always made friends easily while traveling, so how hard could it be?

[Click here to read Part 3]